April 19th

81 degrees — according to the car thermometer.

Positively frigid.

Texas bursts forth in all her warm radiance, wrapping the hills, canyons, and roadsides in bright Spring ribbons. Eight-petaled Englemann Daisies waved their long golden fingers; Indian Blankets spun their flaming copper pin wheels; Prairie Verbena arose in cloudbursts of purple fireworks. Mealy Blue Sage arose and played their role as a bluish-violet Bluebonnet wannabe. I swept past retirement ranches and private oases, watered by dammed up creeks and the Guadalupe River. The whole impression idyllically hypnotic as gurgling water over smooth stone.

Once I left the last of the steep hills behind, the land broadened out revealing the horizon again. The land becomes a wave machine of sorts. Gentle deep dips and smooth rises, the earth rocking you back and forth with long swings as you make your way south. There’s far more rock than grass or trees. It’s hard scrabble countryside that bites back at any plow that dares assault her, yet the stony soil still feeds the soft waves of color erupting along the highway. The road shoulder at last broadened wide enough for me to pull over and take a few pics close to the entrance to the YO Ranch.

Therein lies a tale:

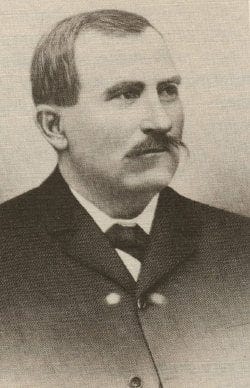

A thirteen-year-old boy’s destiny is changed forever when his family pulls up stakes and moves to San Antonio from Alsace-Lorraine. Charles Armand Schreiner, ripped from all he knew, now must survive the drastic change of scenery — from the land of castles, mountains, and vineyards to the raw, flinty, stabby, scratchy, sweltering land that is the Texas of the 1850’s. Tragedy, never far away from Texas in any era, doesn’t wait to strike. His father dies only three weeks after arriving in the Promised Land. An ill-placed rake or hoe rummaging through brush digs up death in the form of a rattlesnake. It plunges its fangs into the father’s neck. Young Charles now must become a man.

He joins the Texas rangers, doing what young single men do in a time of persistent Indian attacks. Apache and Comanche raids for horses and children continue well into the 1870’s in this region. His poor mother is swept away in an epidemic, even as the thunderheads of Civil War gather on the horizon.

The Schreiner's sympathize with the Union. When the Confederate draft is declared in Texas, Charles’s little brother, Aime, decides that he will head to Mexico with other Union sympathizers. From there they will take a ship to Union occupied New Orleans and continue the good fight from there. Charles thinks about going too. His brother is only a year younger, and they are close. But his wife is 8 months pregnant, and so Charles must choose between the War between the States or a possible war with his wife. He chooses his wife and bids his little brother a heartfelt farewell.

They will never see each other again.

Aime and the other Union supporters are caught around the Nueces River by Confederate forces. A battle ensues. Some of the Union men flee the scene while others stand firm. The Battle of the Nueces becomes the Nueces Massacre when the wounded prisoners are executed by their Confederate captors. Some of the escapees are chased all the way down to the Rio Grande, where they are shot even as they splash across the river. By the time all is said and done, over half of the unit are killed. Aime Schreiner is one of the slain, shot down when he tries to bravely lead a counterattack.

The remains of Aime and the others are buried at Comfort (the hometown of most of them) under a monument that still stands today: The Treue der Union Monument (True to the Union). It’s one of the few Pro-Union monuments to stand in a former Confederate State. Charles names his newborn son Aime after his beloved brother. He also joins the Confederate Army to remove the target from his back. Fortunately the regiment he joins ends up seeing little action.

The young father makes it through the war but now faces crushing poverty as the South begins to rebuild. And so, he does what Texans do best — he reinvents himself.

And man, does he reinvent himself.

He starts up a mercantile store and does so well that, within a decade, he’s able to buy his partner out. He invests in marketing wool and Mohair, helping Kerrville to become the “Mohair Center of the World” for a time. From a broke reluctant Reb, he sprouts into a colossus bestriding the hill country, building up quite an empire woven of business, banking, and ranching.

He purchases the YO ranch in 1880 with the profits he makes from an epic cattle drive of 300,000 longhorns up to Dodge City. The YO will remain in the Schreiner family for six generations, even as other Texas ranches break up and turn into gated communities for California refugees. His grandson, Charles III, reinvents the YO as an exotic game ranch with a regular Noah’s Ark of exotic beasts, earning it the nickname of “Africa in Texas.”

As he nears death, Captain Schreiner makes one last grand gesture, one more legacy to leave behind. He donates money and land to create a military institute for young men near the end of World War I. That military institute, begun in 1923, evolves into what we now call Schreiner University, educating young minds for over a century. Their motto: “Enter with Hope, Leave with Achievement.” I don’t know if young Charles Schreiner entered Texas with hope. But he certainly left it in 1927 with an incredible legacy of achievement. Not too shabby for a poor immigrant kid from Alsace-Lorrain who arrived without a pot to piss in, as my dad would so eloquently say. That’s the flinty stuff Texians are made of.

Leaving the YO behind, I continued heading South to Rock Springs, which is a nice little town mostly devoid of people — which is what made it so nice. The only signs of life are a couple of kids playing basketball after school in their driveway and another three jogging in the cool of the approaching evening along the main road. Other than that, the place appears to be completely deserted. That’s what I really like about this leg of the journey — long stretches of highway with few towns and little traffic. It will prove even more deserted once I get past Del Rio and begin working my way along the river up towards Big Bend. This is more what the real Texas feels like to me. Long stretches of nature and Nothing, with the rare small, sleepy town. The Texas that is fast disappearing.

I can imagine myself sitting out on the square of Rock Springs or some nameless village on the cusp of being legally declared a ghost town, nodding off in the blessed silence, in the blissful haze of deliciously unctuous laziness. Only the infrequent car driving through town awakening me from my well-earned repose before drifting back off to the well-earned oblivion of a warm afternoon. My boyhood home in the country had the same sense of peace stretching out along the boards of our long porch. But my hometown has grown by leaps and bounds since then, suffering the fate of many Texas communities, with neighborhoods of cookie cutter houses metastasizing like cancers, and the roar of traffic over the hill growing louder and louder as taxes and water bills grow higher and higher without a return on the quality of life. “Progress” rampaging throughout a state once known for its open ranges and low cost of living, rapaciously devouring the countryside, sucking the watersheds dry, creating one gigantic Borg-like megalopolis.

As I came within the forty-minute mark of puttering into Del Rio, I realized I was driving down the same road my parents and I meandered down on the way home from Big Bend one year. We’d spent the night in Del Rio after stopping at Langtry to visit the Jersey Lilly Saloon, home of the infamous Judge Roy Bean. I would stop there again this trip. As we drove towards Kerrville from Del Rio, a deer sprang out of the darkness and hit our little blue ford explorer, permanently denting it. Never even saw the deer, it was so dark. So, it could have been a Chupacabra or Sasquatch. My money is on the deer though.

This April trip is a journey into the past in more ways than one, a bittersweet exploration of the beginnings of our vanishing homeland and my own past, reliving memories from those halcyon days before dad went to heaven and Covid tore our society apart all in the same month. Birth and death, endlessly repeating in my mind as the miles and memories fly by. “And so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

I feel in my bones that I am going south, back to the beginning. It’s hard to explain if you’ve never spent much time driving in wide-open spaces, but I can usually figure out my location just by feel without looking at the sun’s position. I’m a ginormous grouchy homing pigeon. I don’t know if those who spend most of their lives trapped in the cages of cities develop that survival instinct.

On and on and on, the miles tick off towards the border, away from places like Austin where newcomers play cowboy in a Texas themed amusement park. Here there’s no pretense, no fakery, just honest simplicity in a harsh environment that doesn’t suffer fools. The endangered Texas.

Lots of roadkill out here too.

Wildflowers have largely died off too, replaced with a mixture of short Spanish oaks and never-ending mesquite groves. I am now in the brush country teetering on the edge of the Chihuahuan Desert. Soon there will only be mesquite. Then just cactus and Ocotillo with their crimson buds like pursed lips kissing the dry air.

Windmills begin popping up on the horizon. Lots of folks hate them. I hem n’ haw back and forth on the issue. I think they can be quite photogenic, especially if they’re planted on a tall mesa and their lights in the evening create their own crimson galaxy of stars against the violent wash of the sky. Or when there’s a storm rolling through, and the towering thunderheads frame the slowly turning arms and lighting plays about her spinning arms in spider webs of angry electricity. But I can also see why people don’t like them. There’s so many of them now. Every lonely butte or mesa or slight rise seem to be giving birth to the things now. I feel like we have more than enough at this point. Leave us a few horizons without a thorny crown of windmills.

At last, I see the edges of Lake Amistad in the distance. The lake is low, so it takes on the appearance of a gigantic canyon stretching out into something like a jagged crater. Quite Jurassic looking. Imagine an abandoned rock quarry with high walls drawn out over miles and miles, and you will have an idea of what Lake Amistad looks like from a distance. Palm trees begin to spring forth as I sight the city limits of Del Rio.

The first rung of my journey into the past now lies behind. Tomorrow I will explore the sacred places of the earliest peoples who called Texas home — well before Father Abraham was even a glimmer in his own father’s eye. Thinking of that makes me think of my dad’s own mischievous twinkling eyes. I begin to miss him again as I drive through town, towards the ancient Rio Bravo.

“And so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”